Having Protocols for Clinical Use to Improve Patient Outcomes

Cheryl Tansley, MS, CCC-SLPT

Gaylord Specialty Healthcare was founded in 1902 as a tuberculosis sanatorium and has grown into a 137-bed long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) facility. Within this facility, specialties focus on the medical management and rehabilitation of patients who have suffered acute illness or a traumatic accident. Because of this focus, programs have been established in Pulmonary, Spinal Cord Injury, Traumatic Brain Injury, and Stroke as major diagnostic areas to provide intervention. Care of these medically complex patients is provided by a multidisciplinary team, including physicians, nurse specialists, respiratory care practitioners, radiology technicians, therapists (physical, occupational, and speech-language pathology), pharmacists, and care managers, for both adolescents and adults. The medically complex populations being seen also may include those patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), restrictive lung disease, chronic emphysema, obstructive sleep apnea, bronchitis, asthma, respiratory complications from morbid obesity, and neurological disorders. Additionally, complex diagnoses also include muscular dystrophy and post-polio syndrome, as well as ventilator dependence due to illness or injury. Because of the wide range and complexity of the diagnoses being treated, a multidisciplinary team is essential to provide best outcomes.

As with many facilities in today’s competitive healthcare domain, it is a struggle to balance patient satisfaction with decreasing length of stays, all while supporting better patient outcomes. Various approaches to patient care have attempted to address the many issues for these patients. The approaches have proven successful, not only at improving patient satisfaction rates, but at expediting ventilator weaning processes and decreasing patient length of stay. The multidisciplinary approach to the care of these complex patients included the development of an Early Ventilator Mobilization Program, increased Passy Muir® Valve use, and Tracheostomy and Ventilator Rounds.

Research has shown that patients with tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation are particularly vulnerable due to the diminished options for mobility, communication, and participation in their care (Freeman-Sanderson, Togher, Elkins, & Kenny, 2018). Not only can this impact a patient’s motivation and psychological state, but immobility through bedrest has been shown to cause a rapid increase in muscle atrophy which may further complicate recovery (Adler & Mallone, 2012). To combat these issues, the implementation of several protocols may assist with improving patient care, satisfaction, and outcomes.

Early Ventilator Mobilization Program Early Ventilator Mobilization (EVM) is an initiative designed to increase activity amongst the patient population with ventilator-dependence. There is no evidence that bedrest has any therapeutic value and often worsens outcomes (Adler & Malone, 2012; de Jonghe, Lacherade, Sharshar, & Outin, 2009; Forte, 2009).

During bedrest, such as occurs in an intensive care unit (ICU), it has been reported that significant changes can occur in both body mass and strength. In his 2009 presentation, Forte discussed that:

- Muscle mass decreases by up to 5% per week.

- Skeletal muscle strength decreases as much as 20% in the first week.

- An additional 20% loss may occur each subsequent week.

- Weakened muscles generate increased oxygen demand.

Even high-intensity bed exercises do not counteract the adverse effects of bedrest. To address these issues with patients who are ventilator-dependent, EVM is a program designed for the physical therapist (PT), occupational therapist (OT), speech-language pathologist (SLP), respiratory therapist (RT), and nursing to be responsible parties in the documentation and mobilization of patients with ventilator-dependence. To increase mobilization, this program includes supine therapeutic exercise, bed mobility, seated balance activities, standing with a walker with assistance, transfers, and upright positioning for meals. All these activities may take place prior to a patient’s ability to be out of bed for walking or moving in the hallways.

The selection criteria for patients, who are candidates for EVM, may be those patients who are:

- Minimally able to participate with therapy.

- Stable hemodynamically.

- Receiving acceptable levels of oxygen.

- Medically stable (sufficient perfusion to maintain normal organ function).

Additionally, acceptable parameters for determining EVM candidates include:

- Heart rate < 110 beats/minute at rest.

- Mean arterial blood pressure between 60 and 110 mmHg.

- FiO2 (Fraction of inspired oxygen) < 60%.

- Maintenance of oxygen saturation > 88% with activity.

The initiative has led all disciplines to have more accountability for mobilizing patients and improving outcomes. This program allows the team to track performance and to have the ability to adjust treatment plans based on trends seen in a patient’s performance. To increase staff communication, a shared documentation site was created to note patient performance with increased activity, including frequency and tolerance of mobilization, and all parties are responsible for the documentation related to the patient’s mobilization. In addition, signs were developed for posting on the doors of EVM candidates to remind all staff to participate in the program and to provide appropriate documentation.

Increasing Use of the Passy Muir® Tracheostomy & Ventilator Swallowing and Speaking Valve

The Passy Muir® Valve (PMV®) is a speaking Valve that is placed on the end of a tracheostomy tube or in-line with ventilator circuitry. It allows air intake to continue though the tracheostomy tube during inhalation; however, air is redirected out through the upper airway during exhalation. The Valve closes at the end of inspiration and remains closed throughout exhalation, allowing airflow out of the nose and mouth, providing readiness for speech production. Studies have supported that wearing a PMV improves true vocal cord closure; restores voicing and communication; restores smell and taste; improves swallowing, by decreasing aspiration risk and restoring subglottic pressure; improves coughing; restores upper airway sensation; restores PEEP, alveolar recruitment to minimize atelectasis; increases gas exchange and improves saturation levels (O’Connor, Morris, & Paratz, 2018). It may also expedite the time to ventilator weaning and tracheostomy tube decannulation by rehabilitating respiratory musculature, increasing confidence and motivation, and potentially decreasing the need for sedating medications (Freeman-Sanderson et al., 2018; Kinneally, 2018; Sutt, Antsey, Caruana, Cornwell, & Fraser, 2017).

Healthcare facilities need to develop the right team, so that all staff are on the same page. This can be done by improving the education of staff and providing research to perspective team members, through readings, demonstrations, and webinars. Adopting a “Ventilator Bundle” order set, where the physician chooses the appropriate bundle, allows for physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy orders for Valve use to generate automatically. Having an order set also reduces the amount of time it would take to obtain the orders to initiate a PMV assessment and assists with getting the team onboard early in the process.

The respiratory and speech departments work collaboratively during both the evaluation and treatment sessions to improve troubleshooting and education. Respiratory and speech therapists work to place the PMV in-line for new patients, who are on a ventilator, usually within the first 24 hours from admission. A team assessment benefits the patient and facilitates success of Valve use because each person contributes a different aspect to the evaluation. Respiratory therapists have a primary focus on the tracheostomy tube type and size, proper cuff management, settings on the ventilator, patient’s vital signs, and safe and proper management of the ventilator and alarms during use of the Valve. The speech-language pathologist focuses on the patient’s ability to voice, their speech and language function, access to communication, cognition, and swallowing. Throughout use of the Valve, all team members maintain vigilance on the patient’s vital signs and status during use.

Many patients and their loved ones have not heard their voice in several days or even weeks but may with use of the Valve. Communicating with family members, significant others, and staff improves a patient’s mood, psychological state, and motivation (Freeman-Sanderson et al., 2018). Lastly, to assist with communicating among the multidisciplinary team members, speech pathology, respiratory therapy, and nursing share a documentation site to note patient tolerance and progress with PMV use.

Establishing Tracheostomy and Ventilator Rounds

Developing a Tracheostomy and Ventilator Rounds Team as a part of the protocol for the care of patients with tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation is another way to enhance team communication and improve the standard of care. This team includes pulmonologists, hospitalists, respiratory therapists, speech pathologists, registered nurses, dieticians, pharmacists, and physical therapists. The Team coordinates all care of patients who are dependent on a ventilator or require use of a tracheostomy tube. Typically, meetings are held one time per week and may take up to an hour, depending on census. The team leader, often an RT, introduces each patient and the team members add to the discussion. Some rounds will incorporate a closed-circuit monitor to review chest x-rays, lab values, and medications, as needed.

In 2016, Gaylord expanded this process to weekly tracheostomy rounding on the rehabilitation and pulmonary floors. Having tracheostomy and ventilator rounds, with participation of a multidisciplinary team, has expedited decannulations (when appropriate) and facilitated better communication amongst the team regarding the plans and goals for the patients. Rounds also ensure the discharge plan is on target by regularly discussing the patients’ goals. Studies have shown that implementing Tracheostomy andVentilator Round Teams improve recovery by increasing the speed at which the ventilator weaning process happens, improving the quality and safety of patient care, ensuring early patient mobility, and supporting early communication (Speed & Harding, 2013; Yu, 2010).

Impact of Change

Challenges to implementing new protocols must be addressed to improve the transition into new processes. It is important to monitor change and conduct Quality Improvement (QI) studies to ascertain the impact. The biggest financial impact realized at Gaylord was seen in the decrease of ventilator days. A ventilator day at the facility costs an average of $1,400. Ventilator days were decreased by an average of 4.33 days. This translated to a cost savings of $6,062 per patient. From 2013-2015, an average of 65 patients were weaned from the ventilator per year. Decreasing the days on a ventilator for this population by 4.33 days translated to a savings of $394,000 per year.

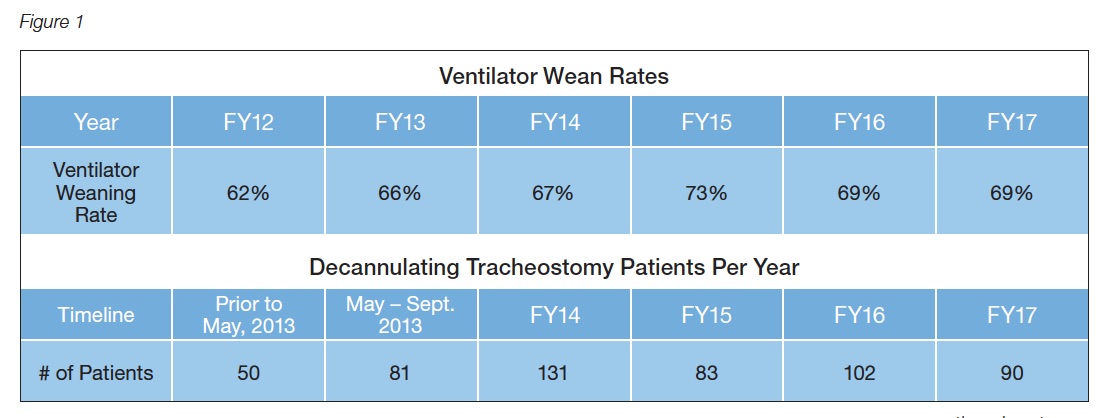

Additional improvements were seen in the consistency of weaning rates and occurrence of decannulation. For this patient population from 2012 – 2017, ventilator weaning rates improved by an average of 6.8% and decannulation rates increased by an average of 447.4 patients per year following implementation in 2012 (see Figure 1).

When these protocols and plans were implemented, patient satisfaction improved, ventilator weaning increased, more patients were decannulated, and length of stay decreased. By working together as a team and implementing protocols designed to improve collaboration and accountability on the part of all staff members, the multidisciplinary team becomes a leader in the care of medically complex patients.

This article is from the Fall 2019 Protocol Issue of Aerodigestive Health. Click here to view Having Protocols for Clinical Use to Improve Patient Outcomes.

References:

Adler, J. & Malone, D. (2012). Early mobilization in the intensive care unit: A systematic review. Cardiopulmonary Physical Therapy Journal, 23(1), 5-13.

de Jonghe, B., Lacherade, J. C., Sharshar, T., & Outin, H. (2009). Intensive care unit-acquired weakness: Risk factors and prevention. Critical Care Medicine, 37(10 Suppl), S309-315 doi:10.1097/ ccm.0b013e3181b6e64c

Forte, C. (2009). Early mobilization of patients in long term acute care settings. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from Gaylord Hospital In-service. 2009 Sept. 28.

Freeman-Sanderson, A. L., Togher, L., Elkins, M. R., & Kenny, B. (2018). Quality of life improves for tracheostomy patients with return of voice: A mixed methods evaluation of the patient experience across the care continuum. Intensive Critical Care Nursing, 46:10-16. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2018.02.004

Kinneally, T. (2018). Do speaking valves reduce sedative drug use in ICU? A retrospective data analysis. Australian Critical Care, 31(2), 131–132.

O’Connor, L. R., Morris, N. R., & Paratz, J. (2019). Physiological and clinical outcomes associated with use of one-way speaking valves on tracheostomised patients: A systematic review. Heart & Lung, 48(4), 356364. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.11.006

Speed, L., & Harding, K. E. (2013). Tracheostomy teams reduce total tracheostomy time and increase speaking valve use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Critical Care, 28(2), 216.e1-10. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.005

Sutt, A. L., Antsey, C., Caruana, L. R., Cornwell, P. L., & Fraser, J. (2017). Ventilation distribution and lung recruitment with speaking valve use in tracheostomised patient weaning from mechanical ventilation in intensive care. Journal of Critical Care, 40:164-170. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.04.001

Yu, M. (2010). Tracheostomy patients on the ward: Multiple benefits from a multidisciplinary team? Critical Care, 14(1), 109. doi:10.1186/cc8218