Los protocolos ayudan a mejorar la comunicación de los pacientes con traqueotomía y dependencia del ventilador

Carmin Bartow, MS, CCC-SLP, BCS-S | Meredith Oakey Ashford, MS, CCC-SLP

Introducción

Para los pacientes con traqueotomía y dependencia del ventilador, la comunicación en la unidad de cuidados intensivos puede ser difícil de lograr, pero tener un medio de comunicación confiable es imperativo para la salud, la seguridad y el bienestar. El equipo de Patología del Habla y el Lenguaje (SLP) del Centro Médico de la Universidad de Vanderbilt (VUMC) lanzó recientemente una iniciativa de mejora de la calidad de seis meses para promover la intervención temprana para esta población de pacientes. El proyecto, "Mejora de la comunicación para pacientes con traqueostomía y dependencia del ventilador", tenía el objetivo principal de establecer coherencia con la comunicación para estos pacientes al capacitar a todo el departamento de SLP en un protocolo recientemente desarrollado. Antes de este proyecto, solo algunos de los SLP en el departamento tenían plena confianza y competencia para brindar intervención a estos pacientes. Con el desarrollo e implementación de este programa, los pacientes pueden participar más fácilmente en su plan médico, lo que puede mejorar la eficiencia de la atención por parte de todo el personal, evitando retrasos innecesarios en su atención, que pueden haber ocurrido como consecuencia de las dificultades anteriores con la comunicación y la participación del paciente.

Propósito

La comunicación deficiente puede generar problemas de seguridad, violación de los derechos del paciente, mala calidad de vida y puede contribuir al delirio en la UCI (Freeman-Sanderson, Togher, Elkins y Kenny, 2018). Algunas de las razones para abordar la comunicación son:

- Problemas de seguridad: los pacientes con problemas de comunicación tenían tres veces más probabilidades de experimentar eventos adversos prevenibles que los pacientes sin tales problemas (Bartlett, Blais, Tamblyn, Clermont y MacGibbon, 2008). Se han informado eventos médicos graves en pacientes con problemas de comunicación (Cohen, Rivara, Marcuse, McPhillips y Davis, 2005).

- Derechos del paciente: La Comisión Conjunta estableció nuevos estándares que se centran en que todos los pacientes tengan satisfechas sus necesidades de comunicación, lo que hace que la comunicación sea una prioridad. La Comisión Conjunta sostiene que los pacientes tienen "el derecho y la necesidad de una comunicación eficaz". En los Elementos de Desempeño para R1.2.100, No. 4 dice, “La organización atiende las necesidades de aquellos con impedimentos de visión, habla, audición, lenguaje y cognitivos” (The Joint Commission, 2010).

- Calidad de vida: la incapacidad del paciente de la UCI para comunicarse puede provocar frustración, enojo, alejamiento de la interacción y reducción de la participación en el tratamiento (Magnus y Turkington, 2006).

- Delirio en la UCI: dos de cada tres pacientes en la UCI experimentan delirio (Grossbach, Stranberg y Chlan, 2011). En un seminario web de la Comisión Conjunta, Llamado a la acción: Mejorar la atención a los pacientes vulnerables a la comunicación, se informó que los pacientes vulnerables a la comunicación tienen un mayor diagnóstico de psicopatología (The Joint Commission, n.d.).

- La promesa de Vanderbilt: “Como institución, VUMC promete incluirlo a usted [el paciente] como el miembro más importante de su equipo de atención médica” y “comunicarse de manera clara y regular, lo cual es primordial en tiempos de enfermedad crítica”.

Métodos de implementación y acceso a la comunicación

Para mejorar la consistencia y estandarización de la evaluación y el tratamiento para el paciente con traqueotomía y dependencia del ventilador, los miembros del equipo SLP que eran competentes con esta población de pacientes:

- Desarrolló un protocolo para estandarizar la evaluación de la comunicación verbal y no verbal.

- Este protocolo comienza con un examen de preparación. Si el paciente pasa la prueba, entonces proporciona un flujo de trabajo para una colaboración entre el patólogo del habla y el lenguaje y el terapeuta respiratorio (RT) durante las pruebas de fonación.

- La colaboración implicaría una evaluación básica del habla, el lenguaje y la cognición y la necesidad de una herramienta simple AAC (comunicación aumentativa y alternativa).

- Difundí este protocolo al personal de patología aguda del habla a través de la enseñanza didáctica, la capacitación personalizada y la verificación de competencias.

- Me reuní con el Director del Centro de Enfermedades Críticas, Disfunción Cerebral y Supervivencia de VUMC para discutir la importancia de la comunicación para los pacientes después de una traqueotomía y ventilación mecánica para minimizar potencialmente el delirio.

- Brindado en servicios a las disciplinas interprofesionales que colaboran en la atención de estos pacientes, que incluyen:

- Terapeutas respiratorios.

- Asistentes y becarios (médicos) de las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos Médicos (MICU).

- Personal de enfermería en VUMC.

- Creé una presentación de póster para un programa de acciones estratégicas en todo el hospital con el fin de difundir aún más el proceso de mejora. El tema de la estrategia compartida de 2019 fue "Diseño para pacientes y familias". Este proyecto CQI encaja perfectamente con este tema y los objetivos de VUMC de mejorar las experiencias del paciente, el médico y el personal.

Resultados

Este proceso cualitativo y la revisión de su impacto proporcionaron un medio para capacitar al personal y revisar el impacto en la confianza y el flujo de trabajo del personal. La revisión de los datos de las entrevistas demostró que la implementación del proceso de mejora mediante capacitación adicional aumentó la confianza del equipo de SLP al atender a esta población. Después de las capacitaciones departamentales en servicio, los SLP comentaron:

- "El servicio me permitió adquirir habilidades y confianza para sentirme más preparado para tratar a estos pacientes complejos".

- "Me siento mejor equipado para manejar a nuestros pacientes de traqueostomía / ventilación".

Además, los terapeutas respiratorios y los patólogos del habla y el lenguaje demostraron un mejor trabajo en equipo para establecer la comunicación para estos pacientes. Se completó una encuesta del personal antes del proyecto para determinar la comodidad y la eficiencia del personal al tratar a estos pacientes. Se está realizando una encuesta posterior a la capacitación. Los resultados preliminares indican que el personal tiene mayor confianza, conocimiento y habilidades para trabajar con estos pacientes complejos.

Además, los terapeutas respiratorios y los patólogos del habla y el lenguaje demostraron un mejor trabajo en equipo para establecer la comunicación para estos pacientes. Se completó una encuesta del personal antes del proyecto para determinar la comodidad y la eficiencia del personal al tratar a estos pacientes. Se está realizando una encuesta posterior a la capacitación. Los resultados preliminares indican que el personal tiene mayor confianza, conocimiento y habilidades para trabajar con estos pacientes complejos.

Lo más importante es que los pacientes que se han beneficiado de este programa manifiestan constantemente su agradecimiento por poder expresarse y participar activamente en su atención. Un paciente dijo: “Ha sido muy frustrante tratar de decirle a mi esposo lo que quiero. No podía leer mis labios, así que traté de escribir, pero no pudo leer mi escritura. Ahora, puedo hablar con él y es mucho mejor ".

Conclusiones

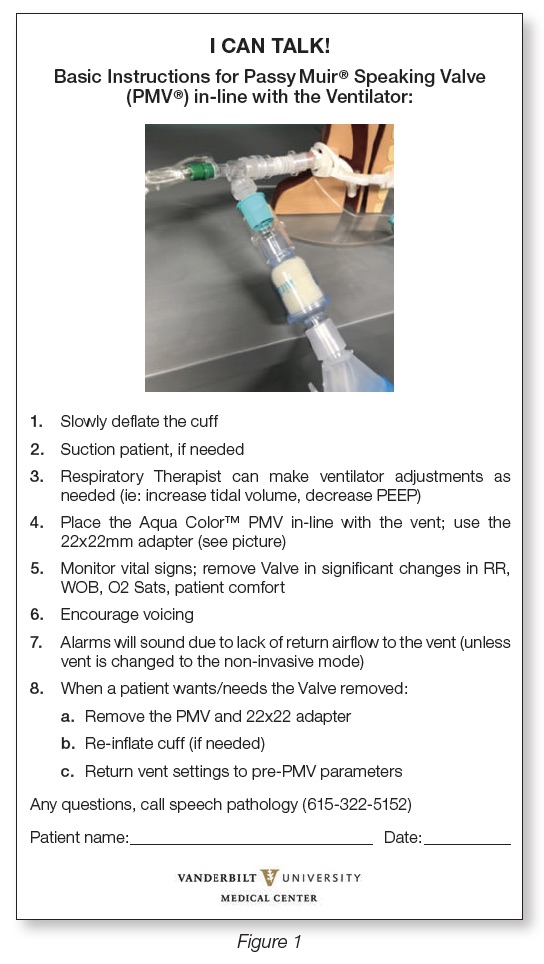

En colaboración con médicos, enfermeras de la UCI, el Servicio de consulta de traqueostomía y terapeutas respiratorios, el equipo de Patología aguda del habla y del lenguaje para adultos está haciendo que la comunicación verbal y no verbal sea accesible para estos pacientes que de otra manera no se comunican. El personal del hospital ahora interactuará de manera más eficiente con los pacientes a partir de esta intervención mediante el uso del signo de la cabecera de la cama recientemente implementado, y les indicará cómo facilitar la comunicación verbal con su paciente (consulte la Figura 1). Este formulario simple mejora la coherencia en la comunicación en todo el equipo interdisciplinario para estos pacientes vulnerables. Mejorar la comunicación con esta población ha resultado en una mejor seguridad, calidad de vida y cumplimiento de las regulaciones de la Comisión Conjunta, las leyes de la ADA y la Promesa para el Paciente de VUMC.

Este artículo es de la edición del protocolo de otoño de 2019 sobre salud aerodigestiva. Haga clic aquí para ver Los protocolos ayudan a mejorar la comunicación de los pacientes con traqueotomía y dependencia del ventilador.

Referencias

Bartlett, G., Blais, R., Tamblyn, R., Clermont, R. J., & MacGibbon, B. (2008). Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178, 1555-1562. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070690

Cohen, A. L., Rivara, F., Marcuse, E. K., McPhillips, H., & Davis. R. (2005). Are language barriers associated with serious medical events in hospitalized pediatric patients? Pediatrics, 116(3),575-9.

Freeman-Sanderson, A. L., Togher, L., Elkins, M. R., & Kenny, B. (2018). Quality of life improves for tracheostomy patients with return of voice: A mixed methods evaluation of the patient experience across the care continuum. Intensive Critical Care Nursing, 46,10-16. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2018.02.004

Grossbach, I., Stranberg, S., & Chlan, L. (2011). Promoting effective communication for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Critical Care Nurse, 31(3): 46-61.

The Joint Commission. (2010). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care: A roadmap for hospitals.[brochure]. Retrieved January 15, 2019 from https://www.jointcommission.org/ assets/1/6/ARoadmapforHospitalsfinalversion727.pdf

The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Call to Action: Improving care to communication vulnerable patient. [brochure]. Retrieved January 15, 2019 from http://www.patientprovidercommunication.org/files/CommunicationVulnerableWebinar.pdf

Magnus, V. & Turkington, L. (2006). Communication interaction in ICU-patient and staff experiences and perceptions. Intensive Critical Care Nursing, 22, 167-180.